150 YEARS SPECIAL DIALOGUE

SPECIAL PROJECT

With prayers,

and with wishes.

Music×Science and Technology

Conductor

Yutaka Sado

President and CEO,

Shimadzu Corporation

Yasunori Yamamoto

Art VS. Science and Technology.

At first glance, one might think they have little in common.

Yet both have enriched our culture and daily lives, supporting them from behind the scenes.

In these turbulent times, the significance of both is certain to grow ever greater.

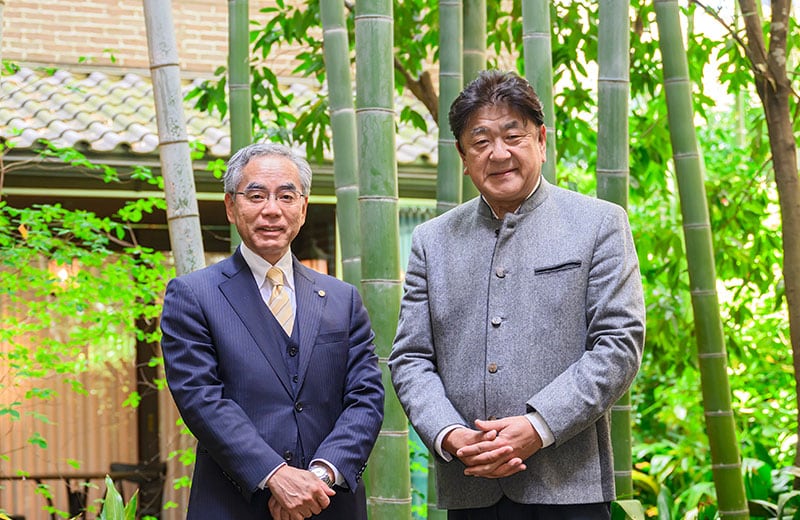

World-famous conductor Yutaka Sado and Shimadzu Corporation President and CEO Yasunori Yamamoto came together to exchange views and perspectives exploring the future of humanity.

Yutaka Sado

Conductor

Born in 1961 in Kyoto Prefecture. Studied under Leonard Bernstein and Seiji Ozawa. Sado won the Besançon International Competition for Young Conductors in 1989, and since then has conducted many leading European orchestras, including the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and the Orchestre de Paris, and continues to be active internationally. Until June 2025, Sado also served for ten years as Music Director of the Tonkünstler Orchestra, Austria’s representative ensemble with over 110 years of history, after which he became the orchestra’s Honorary Conductor. In Japan, Sado holdspositions such as Artistic Director of the Hyogo Performing Arts Center, Music Director of the New Japan Philharmonic, and Principal Conductor of the Siena Wind Orchestra.

Yasunori Yamamoto

President and CEO, Shimadzu Corporation

Born in 1959 in Fukui Prefecture. Yamamoto received a graduate degree in Electromagnetic Energy Engineering from the Graduate School of Engineering, Osaka University, in 1983 before joining Shimadzu Corporation. He became General Manager of the Testing Machine Business Unit in the Analytical & Measuring Instruments Division in 2003, President of Shimadzu Europa GmbH (Germany) in 2013, Executive Officer in 2014, Managing Executive Officer in 2017, Director and Managing Executive Officer in 2020, and Director and Senior Managing Executive Officer in 2021. He has held his current position since 2022.

Where did music come from?

Yamamoto: Thank you for coming today.

Sado: Thank you very much for inviting me to this special occasion celebrating your 150th anniversary.

I was born in Kyoto, and to be honest, as a child I used to play baseball in the park right next to Shimadzu. I feel a mysterious sense of connection.

Yamamoto: Is that so? Well, I have a confession of my own too. When I was a student, I belonged to a choir and even served as a conductor. Since you, Mr.Sado often conduct choral works, and I’ve enjoyed listening to your music for a long time, I’ve always hoped I’d have a chance to meet you.

Sado: I see, you’ve conducted a choir, and now you’re conducting a corporation!

Yamamoto: Yes [laughs]. There might be some similarities between the two. Shimadzu is not an orchestra, but within the company there are many parts, or roles to play, and I often encourage our employees to bring out their strengths and devote themselves to their roles to achieve greater harmony.

Sado: I’m quite certain I could never conduct a corporation [laughs].

[both laugh]

Yamamoto: If you don’t mind, there’s something I’ve been wanting to ask you, Mr. Sado. The field of science and technology, which we are engaged in here at Shimadzu, stem from a deep interest in nature and life. I believe these always been close to humanity, even since ancient times.

Take, for example, cave paintings. Before anything was drawn, there must have first been a desire, an urge to express something. To fulfill that desire, people would have realized they needed tools or materials to draw with. And in creating those materials, they would have gone through many trials and errors, making adjustments along the way.

Eventually, through repeated effort, they succeeded in painting on the cave walls. I believe that by accumulating such desires, failures, and innovations, and gradually systematizing them, we arrived at what we now call science and technology.

And what about music, how do you think it originated?”

Sado: That’s a rather difficult question. I’m not a scholar, so I’ll respond without anthropological or historical references. But I think ancient music arose because of a desire to express emotions and excitement. Adding rhythms and modulation can be just as expressive as words, or even more so.

Yamamoto: I see. Music certainly has the power to move the heart.

Sado: From there, melodies gradually emerged, giving rise to the concept of music itself. And for music to be counted as a part of culture as it is today, I believe there were two major turning points in music’s history.

Yamamoto: What were they?

Sado: One was encountering religion. People began to notice that the power of music could be effective in spreading faith, and started using it actively. Christian music is a clear example, but even Buddhism and Islam include musical elements. I imagine that as a result, people with musical skills became more valued, and more people started wanting to be involved in music.

Yamamoto: Interesting.

Sado: Another critical event was the development of musical notation. I think this was a great invention. Musical sheets allow different people to play the same music again and again. They allow musical ideas to transcend distance and time. Today, I can perform works by Mozart or Beethoven thanks to musical notation.

Yamamoto: You are exactly right. In my youth, I too used to study sheet music so closely it felt like I was staring holes into it. I believe sheet music reflects the soul of the composer. You conducted Beethoven’s Ninth (Symphony No. 9 “The Ode to Joy”) for the opening of Expo 2025 Osaka, Kansai, Japan. I heard that around 10,000 people joined the chorus.

Sado: Yes. I’ve had the honor of conducting several performances of the Ninth with ten-thousand-person choruses, but doing it for the opening of the Expo made it especially meaningful. Are you familiar with the lyrics?

Yamamoto: Yes, of course.

Sado: The lyrics of the Ninth Symphony speak of people from different backgrounds and ways of life becoming brothers through a kind of magical power.

But it also says some pretty strong things, especially the phrase, “Embrace one another.” The lyrics say that unless we embrace each other, we cannot truly be brothers. To me, it felt as though the lyrics are describing today’s increasingly divided world, almost like a message of encouragement directed at all of us.

Yamamoto: You’re absolutely right. Perhaps now is the time when the Ode to Joy should be sung throughout the world.

Communicating the shared joy of living

Yamamoto: I notice that you actively conduct outside the concert hall, like with this performance of the Ninth at the Expo, community concerts, charity events and so forth. Is there a particular reason for this?

Sado: During the Great East Japan Earthquake, I had an unforgettable experience. Just after the disaster, police officers, firefighters, the Self-Defense Forces, doctors, and drivers delivering relief supplies were all doing incredibly noble work. I too wanted to help those who were suffering and grieving, but what can a musician do? I was overwhelmed by a sense of helplessness. About five months after the earthquake, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to conduct a concert on the coast of Iwate Prefecture, where the scenes of destruction left by the tsunami were still painfully visible. Alongside classical pieces with themes of prayer, I mixed in Japanese compositions that were familiar to older people in the audience, hoping to lift their spirits even a little as I conducted. And then, everyone began to sing along. They were moved to tears and expressed such joy. I was deeply touched as well, and it stirred something in my heart.

What is music, really? Music is nothing more than vibrations in the air around us. Compared to medical care or food aid, it has very little power. But by sharing it in the moment, music made us feel that we were together. I came to believe that music exists to help people feel the joy of living together, of sharing life with others.

Yamamoto: That must have been quite an experience.

Sado: Since I’m a conductor, my true role is to correct pitch, adjust tempo, and create beautiful phrases and harmonies. When I was younger, that is what I did—I focused on making the best music I could. Now I pay much more attention to conveying the joy of living through music.

Dreams do come true

Sado: I once had a chance to visit your research laboratory, andI have to say, I was truly impressed.

Yamamoto: Ah, you must be referring to theTechnology Research Laboratory in Keihanna.

Sado: What really surprised me was that Shimadzu is doing research into ‘excitement.’ Delivering excitement is what we musician do, so we might not be so eager to see such a thing explained scientifically [laughs]. Yet listening to the explanation I was given, I found myself fascinated.

Yamamoto: [laughs] Hearing that from an artist like yourself really means a lot to us.

Sado: I’d be really interested to hear more about the research, could you share a bit more?

Yamamoto: Of course. Let me ask you, where do you think your heart is?

Sado: In my brain, I suppose.? I’m not entirely sure what this thing called the mind actually is, but emotions are governed by the brain too, aren’t they?

Yamamoto: We at Shimadzu think so as well. But no one knows whether it’s truly a job for the brain alone.

Sado: Is that so?

Yamamoto: Looking back through history, the human body has always been one of humanity’s great fascinations. Countless scientists and doctors have studied how the body moves, how it perceives sound, and so much more. Yet despite all the research, there’s so much we still don’t understand.

Sado: I see what you mean.

Yamamoto: And among of all that, the brain remains the least understood part of all, especially when it comes to emotions like awe and empathy since no one truly knows how they arise. Traditionally, we have thought that thinking takes place in the head, while emotions are felt in the chest, around the heart.

After all, we instinctively place our hand over our chest when talking about feelings. And maybe that intuition isn’t entirely incorrect.

Sado: Oh, really?

Yamamoto: Here’s an example. When we listen to music, sound enters our ears and is converted into electrical signals, which are sent to the brain. It’s possible that the sensation of air vibrations felt by the skin, or the expression on your face seen with the eyes, are also transmitted to the brain as electrical signals. Now, those signals don’t go to the brain alone. They spread throughout the body. That’s how we might be moved to tears, feel our heart beat faster, or smile spontaneously. We believe that these physical responses resonate together, and it is this resonance that the brain recognizes as emotion.

Sado: Resonance? Is that like every part of the body acting as part of an orchestra?

Yamamoto: “The body as an orchestra.” I like that.

Sado: You’re a true dreamer.

Yamamoto: To hear you say that is a great honor. I believe that what science and technology offer us are the dreams of humankind.

Sado: You’re right, science and technology have realized many of humanity’s dreams.

Yamamoto: Yes, such as abundant, healthy daily lives. For all of recorded history, humanity has had dreams, and science and technology have progressively made those dreams reality. But it all depends on how science and technology are used. They’ve also been used to create weapons that can destroy humanity. So rather than say that science and technology give us things, it might be more accurate to say that there are things we hope to be given by science and technology. I sincerely hope science and technology will remain essential tools to realize the dreams humanity has yet to achieve, even those dreams we can’t see yet.

Sado: I hope so too.

Yamamoto: Thank you for meeting with me today.

Venue : Fortune Garden Kyoto (The former head office building of Shimadzu Corporation)

With prayers,

and with wishes.

Music×Science and Technology

Conductor

Yutaka Sado

President and CEO,

Shimadzu Corporation

Yasunori Yamamoto