A Clock for Redefining Time

Optical Lattice Clock Accurate to 1 Second Every 10 Billion Years

An extremely accurate optical lattice clock that deviates by only up to 1 second per 10 billion years is now offered as a commercial product for the first time in the world.

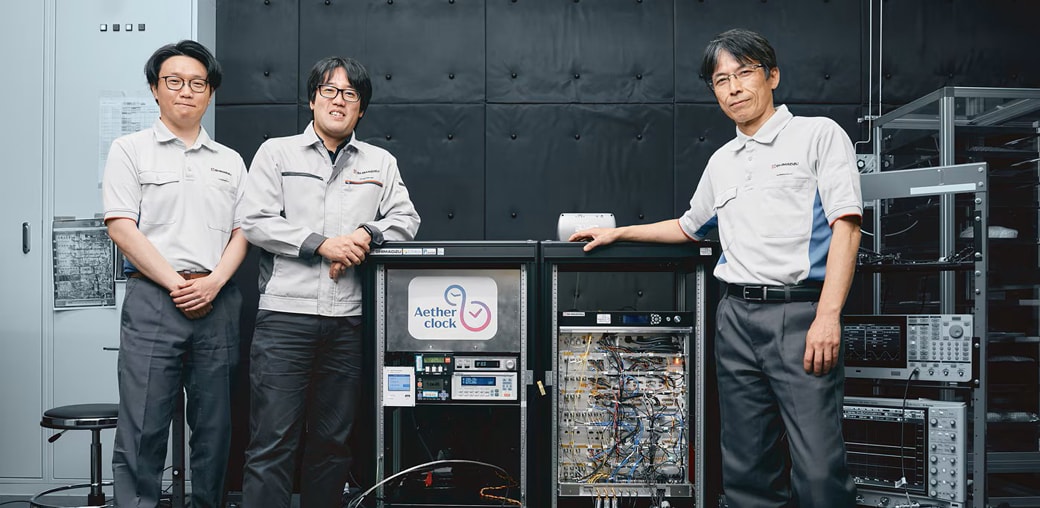

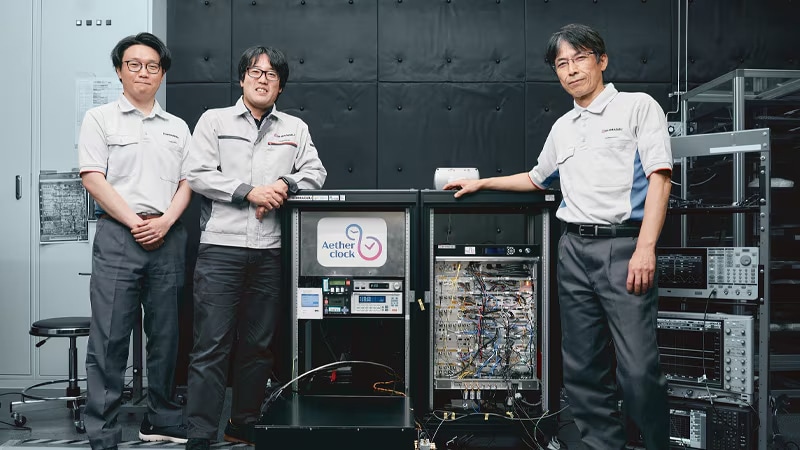

Asking the development team at Shimadzu Corporation about the history leading up to the release of the clock, which is named the “Aetherclock OC020,” and what the future expectations are for the clock.

Demonstrating the Theory of General Relativity on a Day-to-Day Scale

“Does Shimadzu want to participate in an optical lattice clock project?”

That question by Professor Hidetoshi Katori from the Graduate School of Engineering, the University of Tokyo, aroused excitement in employees at the Shimadzu Corporation Technology Research Laboratory.

An optical lattice is a lattice-shaped grid of laser beams that is used to trap atoms for measuring the vibration from their interaction with the light. Strontium atoms are trapped in the lattice like orderly rows of eggs in an egg carton. Because each type of atom vibrates at its own unique frequency, the vibration frequency can be used as a reference for time. However, accurate values cannot be determined from measuring only one atom, so an average value from a million measurements must be determined. Measuring the atoms one at a time would take massive amounts of time, so the vibrations of a million atoms are measured at the same time to instantaneously determine the average. That is the essence of Professor Katori’s revolutionary invention.

Optical lattice clocks offer accuracy to 18 decimal places, which is significantly more accurate than the 15-digit accuracy of cesium atomic clocks currently used as the reference for defining the “second.” Achieving an accuracy equivalent to a 1-second error every 10 billion years resulted in Professor Katori being named as a leading candidate for winning the Nobel Prize in Physics.

However, when Professor Katori contacted the Technology Research Laboratory about the optical lattice clock in 2015, the clock was large enough to completely fill a large laboratory room. That meant it would be essential to shrink its size before it could be used widely in society.

Koji Tojo, Deputy General Manager of the Advanced Analysis Unit at the Technology Research Laboratory, recalled that “At that size, it was too big to take outside the laboratory for use in field experiments, so the professor asked us to help reduce its size. In particular, since the portion of the clock that consumed the most amount of space was the laser control circuitry, he wanted us to be in charge of making that portion smaller.”

The goal at the time was to conduct an experiment to measure the time difference between optical lattice clocks installed on the ground floor and the observation deck of the Tokyo Skytree tower. The aim was to demonstrate, at an everyday scale, that “time progresses more slowly at locations with higher gravity (lower elevations),” as indicated by the theory of general relativity.

That experiment would require reducing the clock size from a system that filled a room to something small enough that it could be transported to the Skytree and carried up the tower. As a result, they formed a team within the Technology Research Laboratory and formally started the project. That was in 2017.

Koji Tojo, Deputy General Manager, Advanced Analysis Unit, Technology Research Laboratory

“At first, it seemed like we were blindly groping in the dark. We needed to configure control circuits based on our interpretation of hand-drawn drawings provided by Professor Katori. There were so many things that needed to be accomplished and the accuracy level required was extremely high. We could barely keep up,” recalled Takashi Muramatsu, who was assigned to develop the hardware. In addition to lasers for forming the optical lattice, the optical lattice clock required extremely precise control of all lasers—including those used to cool strontium atoms from a high-temperature state to nearly absolute zero and those tuned to a single frequency for measuring atomic vibrations—and the entire system. The requirements were so difficult, even now Muramatsu describes it as “be horrified.” As a result, they created easily over 100 circuit boards.

Despite those challenges, a year later, the team had reduced the size to a volume of 920 liters, which is about 1/20th of the original size. Regarding the amount of work involved to that point, Muramatsu said, with a wry smile, “When I think about it now, it is scary how much we worked. Without a doubt, it is the hardest I have ever worked in my career.”

Takashi Muramatsu, Assistant Manager, Laser Applications Group, Advanced Analysis Unit, Technology Research Laboratory

In 2018, the optical lattice clocks were carried into the Skytree tower, and an experiment was started. After about six months of conducting the experiment, they measured that time was progressing 4.26 nanoseconds per day faster on the observation deck than at the ground level. That is equivalent to a time difference of about 4 seconds after about 3 million years. However, more than the numeric value, the measurement’s true significance is that they were able to measure distortions in the space-time continuum from a commonplace elevation difference of only 450 meters, rather than having to place a cesium atomic clock in a rocket or satellite to measure time differences between space and the Earth’s surface.

“To Professor Katori, the Skytree experiment was merely a demonstration for promoting more widespread use of the clock in society. He was looking much farther ahead.” (Muramatsu) Then, without taking a break, the team embarked on a new chapter.

Enter a New Stage of Commercialization

The new stage arrived when the clock was selected for the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) JST-Mirai Program “Space-Time Information Platform with a Cloud of Optical Lattice Clocks.” The project involves installing optical lattice clocks at various locations throughout Japan and connecting them via the cloud as a platform for space-time information. Rather than relying on the global navigation satellite system (GNSS) or other methods, the platform would establish an infrastructure for more accurate positional information that could be used to provide a real-time understanding of tectonic plate and ground movements throughout the Japanese archipelago for detecting precursors to earthquakes and volcanic activity.

Tojo recalled that “The project required commercializing an optical lattice clock, so that is what Shimadzu put in charge of. It shows how much they trusted us, but looking back now I think that at that point we were still underestimating the difficulty of the process.” People say that between experimental technology and commercial application is a “valley of death” with a gaping mouth. As it turned out, the team members eventually got to experience first-hand just how deep that valley is.

Though Shimadzu’s team was mainly involved in the control circuitry of the experimental unit, commercialization required the team to also be involved in controlling the lasers themselves and their overall configuration. Therefore, it added team members from the Technology Research Laboratory’s Photonics Group, who had been working with lasers, thereby expanding the team. Tojo also has experience researching blue lasers for many years.

Tojo shared that “As soon as I first started working with Professor Katori, I felt he was both a super scientist and super engineer who would thoroughly think things over in terms of multiple stages, ranging from generating ideas to promoting broad adoption of those ideas. He also has extremely extensive knowledge about lasers. I was especially impressed with the fact that he was already thinking about solutions for commercialization challenges.”

The challenge at the time was the limited lifetime of blue lasers for cooling. The high energy level of blue lasers led to an accumulation of fine particles, which caused the lasers to start malfunctioning in only two to three months. While maintenance after short periods might be tolerable for experimental use, it is unacceptable for commercial use.

“The method used for Professor Katori’s optical lattice clock involved successively irradiating not only blue lasers but rather six different types of lasers for cooling and measuring. To be honest, given that I struggled with only one blue laser, the high difficulty level of the challenge made me feel like I was not getting involved (laughed). However, it is strange how talking to the Professor mysteriously makes us feel we can solve the problem.” (Tojo)

Irradiating six lasers with different frequencies on strontium atoms in order to cool and measure them requires extremely precise control. After trying a wide variety of methods, they were able to overcome each challenge, one at a time, but then that generated even more issues.

Yuya Sakai, who was in charge of the software, explained that “If the wavelength of any one of the six lasers shifts out of adjustment, it could prevent the system from functioning as a clock. Having to retune the lasers each time they shifted out of alignment would be unacceptable for a commercial product. Therefore, we included software that can automatically reset condition settings.”

Yuya Sakai, Assistant Manager, Laser Applications Group, Advanced Analysis Unit, Technology Research Laboratory

Furthermore, previous optical lattice clocks were so sensitive to changes in the external environment that simply closing the laboratory door would cause measurement results to vary. During the Skytree experiment, Sakai and others even experienced situations when the clock stopped functioning properly due to vibration from the subway. Therefore, they developed software with a unique algorithm to provide functionality that automatically restores proper clock operation.

“We were also helped by hardware that offers very consistent operation. That also helps ensure the software functions properly. It gave us the impression that the system started out with a very good basic design.” (Sakai)

Overcoming Their Own Challenge of Reducing the Size

The greatest challenge was achieving a smaller size. The clock size was reduced to about 1/20th of the original size by the time of the Skytree experiment, but to develop the clock as a commercial product, their goal is to reduce the size by half again to 400 liters. In addition, that target value decreased to 250 liters in 2020.

“The initial 400-liter goal was already rather high, so in order to shrink the portion of the clock made by Shimadzu as much as possible, we reduced the number of circuit boards in the control system from over 100 to 1/5th that quantity. That successfully shrunk Shimadzu’s portion by about 100 liters, so maybe 250 liters would be possible after all. It seems that we raised the bar for ourselves, doesn’t it,” remarked Muramatsu while scratching his head. Consequently, the space available for wiring and other components is very limited, which seems to have caused extra work.

By carefully reassessing the entire design, creating separate modules for each function, and developing and testing the modules separately, they were successful in increasing the development speed. However, added to their burden of development was the greater-than-expected expectations placed on them from the broader public.

“After the visit by Japan’s then Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and expressions of encouragement from so many people, I was really feeling the weight of that responsibility. However, the project was very consistent with Shimadzu’s corporate philosophy ‘Contributing to Society through Science and Technology,’ so we increased our effort level even higher.” (Tojo)

Then, in April 2025, Shimadzu’s team finally released the world's first optical lattice clock. In 2026, a General Conference on Weights and Measures is scheduled for preparing a new definition of the second. It is important that the clock is widely accessible at that time in order to be selected as the reference clock for defining the second after 2030.

The Aetherclock OC020 strontium optical lattice clock, downsized compared to the experimental unit, enables measurements outside of a laboratory. Its functionality for automatically restoring operability can significantly reduce previous labor-intensive processes involved in restoring operations

Shimadzu has already received multiple inquiries from research institutions and others around the world and have begun moving toward optical lattice clocks being used as the new de facto standard.

Tojo went on to say “Though I think we have achieved the targeted performance and usability levels, there are still many improvements to be made. For example, we need to achieve a longer service life for lasers and increase robustness with respect to vibration and other external influences. By continuing to make such improvements, I am confident the clock can make even more contributions to society as a clock necessary for society, such as for providing infrastructure and researching disaster prevention.”

Humanity is now about to start marking time in a new way.

Project team at Technology Research Laboratory standing with the Aetherclock OC020 Optical Lattice Clock

- *This article is an English translation of our article originally published on the website “Boomerang”. The information, including affiliates and titles of the persons in this article, are current as of the time of interviewing.

Copied

Copied