The Future of Medicine: Thus Let It Be

“We will gladly undertake the manufacture of whatever you may request of us.”

The aim was to reproduce the experiments in which X-rays were successfully generated in Germany.

Social implementation was also the goal.

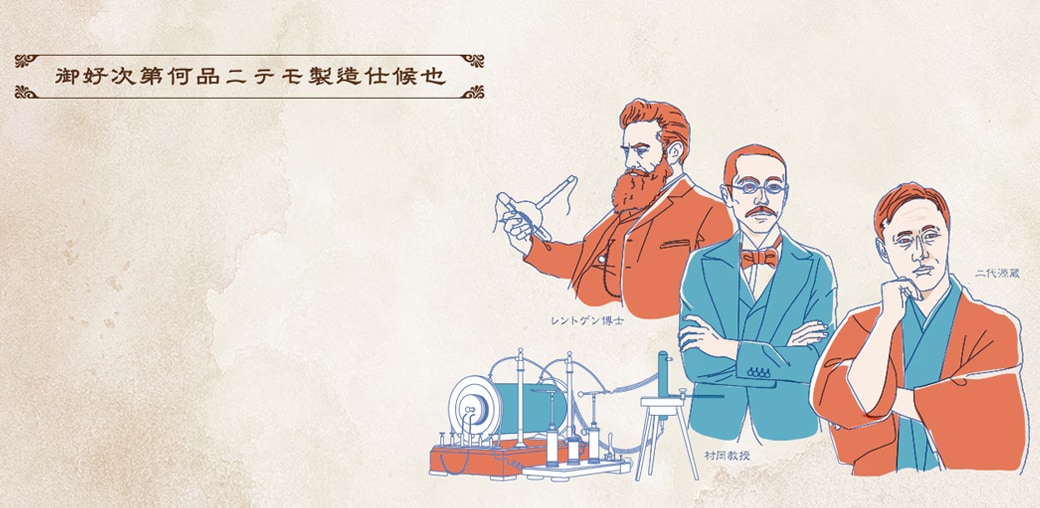

This is the story of a Japanese physicist and Genzo Shimadzu Jr. responding to his aspiration.

Discovery of Penetrating Light Rays

“Light that penetrates the body and reveals its interior has been found.”

In January 1896, this momentous news shook the world. This news was about the discovery of X-rays by Wilhelm Roentgen, a German physicist.

Someone who was particularly happy about this information lived in Japan. He was Professor Hanichi Muraoka, and at the time, he worked at The Third Higher School (predecessor to Kyoto University) in Kyoto.

Muraoka had been known as a genius since he was a boy.

In 1878, then 25-year-old Muraoka was dispatched to the University of Strasbourg in Germany under a mandate of the Meiji government to investigate normal schools in Europe and the U.S. In the laboratory where he worked, he studied the science of acoustics.

In this acoustics laboratory, Muraoka was to have a fateful encounter. It was none other than Wilhelm Roentgen who was serving as an assistant professor there. Roentgen was eight years Muraoka’s senior, and Muraoka formed a close bond with Roentgen, regarding him as a mentor. To Muraoka, Roentgen was no doubt a model of what a man of science should be.

As spring approached, scientists around the world set about trying to repeat Roentgen’s experiment.

Muraoka too wished ardently to be the one to reproduce the experiment. X-rays had the potential to overturn the medical consensus of the time. They could reveal not only skeletal structures, but also perhaps organs, all without using a scalpel. Furthermore, X-rays were discovered by Roentgen, whom Muraoka had apprenticed himself to while studying abroad in Germany nearly 20 years ago. This was likely why he had the idea of reproducing the experiment with his own hands.

Muraoka accepted the mandate from the government, and set about experimenting. However, it did not go well. With the power sources and induction coils of the time, the voltage was insufficient to generate X-rays. At the time, power was a precious commodity. It was not like today, when stable electric power can be accessed simply by inserting a plug into an outlet anywhere. Electric power was limited to only a few areas such as urban centers. Moreover, reproducing Roentgen’s experiment required a high voltage of at least 200,000 volts.

An Encounter between a Genius and an Inventor

“If I had the electricity from the exhibition, the experiment would be possible.”

In 1895, Muraoka remembered a product from the 4th National Industrial Exhibition held in Kyoto. It was a generator built by Umejiro, the son of Genzo Shimadzu Sr., the founder of Shimadzu. At the age of only 15 in 1884, Umejiro had built a Wimshurst electrostatic generator, relying solely on a schematic introduced by the British inventor James Wimshurst. After repeated improvements, he had provided it for use in the fields of education and research. One of these instruments was shown at the exhibition. (Umejiro inherited the name Genzo following his father’s untimely passing away in 1894.)

Muraoka paid a visit to Genzo Shimadzu Jr. and asked for his cooperation in reproducing Roentgen's experiment.

Certainly, Genzo had no doubt heard news of the discovery of X-rays. He no doubt held hopes for the development of medicine with a light that sees into the human body.

“Let’s do it.”

Genzo smiled and took Muraoka’s hands.

In early summer of 1896, at the Shimadzu Corporation serving as the laboratory for X-ray photography, Muraoka and Genzo made repeated attempts to reproduce the experiment.

They had solved the power supply problem, but difficulties with the other parts continued. The vacuum tube that generated the X-rays was a very precious item and was ordered via a Japanese doctor who was studying in Germany. The photography was particularly problematic. At first, they did not think of placing the subject on top of the dry plate, which served as the film. Instead, the two were set at a considerable distance from each other, and the dry plate was carefully wrapped in paper to keep out the light. Even then, there was a risk that sunlight would seep in, and so the experiment was repeated only at night. However, success did not come easily. As X-rays had only recently been discovered and their properties were still not well understood, one can well imagine the hardship of experimentation in those early days.

The days stretched on, and autumn arrived.

Early on the morning of October 10, the experiment was repeated after dozens of attempts. A one-yen silver coin was placed in a paulownia-wood box, with a dry plate set under it, and the induction generator was kept running for several tens of minutes. As a result, a vague image of the silver coin was formed. This achievement came 11 months after Roentgen’s success with X-ray photography in Germany.

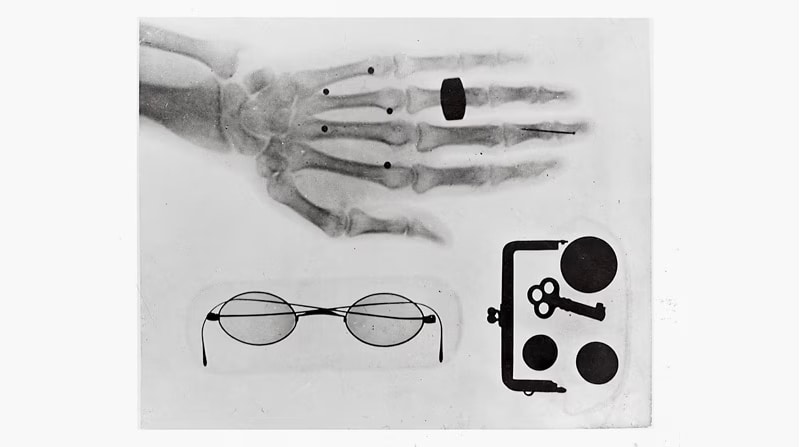

Hanichi Muraoka had promised to deliver the first successful X-ray photograph to his mentor at the Imperial University. Genzo later recalled, “I took a 24-hour train journey to Tokyo and presented the photograph to Professor Kenjiro Yamakawa.”* For this reason, the photograph produced at that time has not been preserved. Later, with successive improvements and experiments, the resolution of the X-ray photograph increased day by day. This photograph shows Muraoka’s eyeglasses, a coin pouch, and the hand of their assistant, Munesuke Kasuya.

* Hiroshi Ishiyama (1971), “The Child of a Blacksmith who Became a Manufacturer of Physics and Chemistry Instruments: Genzo Shimadzu”, Hisaharu Tsukuba and Toshiyoshi Kikuchi (Eds.), Meiji no Gunzō, Vol. 7, p. 205.

Science Finds Meaning in Society

Naturally, Genzo did not ease his efforts at this point. Later, he changed the power supply batteries in various ways to obtain a higher, stable voltage. He repeatedly modified the induction coil itself, enhancing its discharge power, and thus succeeded in producing clearer X-ray photographs. Further, he also began development of a fluorescent plate capable of observing the interior of a subject in real time. He tested numerous chemical substances on glass plates and eventually succeeded.

Based on the fruits of these experiments, he commercialized the instrument and released an educational X-ray apparatus in 1897. He created a pamphlet and distributed it to the educational community, where it received such an enthusiastic response that it had to be reprinted twice. The contribution he made to the educational community at that time was by no means insignificant.

Accordingly, in September 1909, a medical X-ray system, completed entirely with Shimadzu’s own technology, was delivered to the army Kohnodai Garrison Hospital in Chiba Prefecture. This was the first such system produced in Japan. Two years later, he delivered a large medical X-ray system, based on an induction coil that used a rectifier to convert AC into DC, to the Japanese Red Cross Shiga Branch Hospital in Shiga Prefecture. He continued to introduce groundbreaking instruments to the world.

At the same time, in the medical community, acquiring correct knowledge of X-rays and training technologists with this specialized knowledge had long been a desire. As the instruments became more widespread, Genzo believed that the training of such technologists was indispensable for the development of medical treatment. Accordingly, in 1927, the Shimadzu X-Ray Technology Training Center (currently Kyoto College of Medical Science) was established with the permission of the Kyoto Prefectural Governor. It became the first private institution to train diagnostic X-ray technologists.

The future that Muraoka and Genzo had envisioned was finally a reality.

Genzo had faith.

“If you learn a scientific principle, you must also consider its applications. Learning should be practical.”

In 1930, he was selected as one of Japan’s ten greatest inventors. His tireless commitment to practical implementation, working alongside researchers, has been carried on by Shimadzu to this day.

- *This article is an English translation of our article originally published on the website “Boomerang”.

Copied

Copied