A Dream of Flight

“We will gladly undertake the manufacture of whatever you may request of us.”

The power of imagination is limitless. What if we could do....?

What if the future were like...? People dream up ideal futures.

150 years ago, in Kyoto, someone envisioned a future in which people could fly.

Genzo Shimadzu Sr., the founder of Shimadzu, took it on himself to make this a reality and challenged himself to create such a future.

An Unexpected Request

“Could you build a balloon for us?”

In front of his shop in Kiyamachi-Nijo, Kyoto, Genzo Shimadzu greets someone and is left speechless by his request.

Genzo has heard of balloons. It must be a sphere that can fly. However, he has never seen such a thing, and he is not even sure of the theory behind how it would fly.

Yet by then, Genzo had already recreated with his bare hands some of the wonderful tools produced in the West, and the almost magical phenomena that could be produced with such tools. So, he found the request interesting, and it sparked his curiosity.

“Kindly leave these illustrations with me please.”

The man handed over the drawings, and Genzo eagerly studied them.

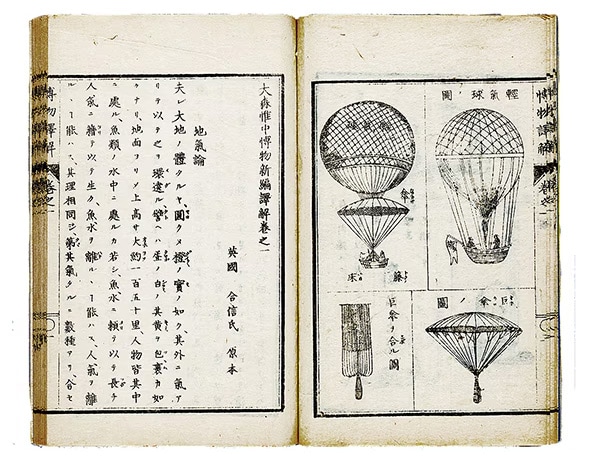

Ichu Omori’s “New Encyclopedia with Technical Interpretation” provided both a simple overview of the principles behind balloons and accompanying illustrations. Reference: Union Catalogue Database of Japanese Texts (Archives of the National Institute of Japanese Literature) 1874, new and revised edition

An Influx of Knowledge and Technology

The mid-19th century was an era of major change for Japan. It all started in 1853 with the arrival of the American naval fleet or so-called “black ships,” after which the Edo Shogunate made a significant policy shift toward the opening of Japan. Japan was eager to obtain knowledge from other countries, so many foreigners were employed as teachers, and Japanese were dispatched internationally as overseas students.

Knowledge and technology flowed into Japan as if a dam had burst.

During this, in 1868, the era was renamed to Meiji, signaling that a new era had begun. But for Kyoto, which has been the capital of Japan for a thousand years, the Meiji Revolution proved to be a time of great trials. In the Kinmon Incident (1864), fought between the Choshu and the Shogunate, 3/5th of Kyoto’s streets was razed. And in 1868, these wounds had not yet healed when the Emperor changed residence from Kyoto to Edo (Tokyo) in accordance with the change of era. The people of Kyoto were deeply disappointed.

Such was the era in which Genzo Shimadzu, the founder of Shimadzu, found himself.

Genzo was born in 1839. His father, Seibei, had moved to Kyoto from what is now Fukuoka Prefecture on Kyushu Island. In Kyoto, he opened a shop selling equipment for Buddhist altars. Following his death, Genzo inherited the business and started a blacksmith’s shop for manufacturing Buddhist altar equipment in Kiyamachi. This was in 1860. The great fire resulting from the Kinmon Incident encroached as far as the adjacent shops in Kiyamachi. Although his shop just narrowly escaped the fires, the people in his neighborhood were sufficiently preoccupied that they no longer had any interest in Buddhist altar equipment. A decree in 1868 to separate Buddhism from Shinto led to a movement to abolish Buddhism to reduce its power, and the Emperor left Kyoto. Genzo could see absolutely no way ahead.

An Encounter with Western Science

But Kyoto was not dead. The people responsible for Kyoto administration acquired significant funding for reconstruction from the central government as compensation for the relocation of the capital. These funds were provided to private sector companies in order to promote the reconstruction of the city. Together, they painted an image of Japan’s future based on enhanced production and industry.

Two years after the start of the Meiji period, Genzo’s life chanced upon a path leading to this future for Japan.

A facility known as Seimi-kyoku (The Physics and Chemistry Research Institute), which was built by Kyoto Prefecture, was only a few minutes on foot from his shop in Kiyamachi. The word “Seimi” was derived from “Chemie,” the Dutch word for chemistry. This laboratory for industrial physics and chemistry of the time performed manufacturing and quality tests on minerals, medicines, and beverages, and provided education for the students who gathered there. Genzo, with his keen interest in the new and a strong inquisitive nature, visited whenever he was not busy with work. There was also a printing press there, and glass, silk thread, soap, and beer were manufactured on-site. Genzo attended lectures on physics and chemistry and performed experiment after experiment. The Western equipment, which was totally new for him, and scientific knowledge certainly must have had a tremendous effect on him.

Ultimately, he received high praise from the Physics and Chemistry Research Institute for his manual dexterity and metalwork techniques, cultivated as a maker of Buddhist altar equipment. He then began repairing and preparing Western equipment, and manufacturing tools for use in experiments and lectures. Genzo, who was able to create things one by one relying just on book illustrations, became an indispensable manufacturer as far as the Physics and Chemistry Research Institute was concerned.

The number of students enrolled at the Physics and Chemistry Research Institute increased, and physics and chemistry school programs began to be taught. Science had cleared the way forward. Masanao Makimura, who, as Kyoto Prefectural Governor at the time, had played a key role in establishing the Physics and Chemistry Research Institute, wished to see this become an even bigger movement.

Serving under Makimura was Sennosuke Harada, who worked as a department head at the Kyoto Educational Affairs Office. A zealous proponent of physics and chemistry education, he wished to use specific examples to raise the level of scientific thinking and to boost the spirits of the people of Kyoto Prefecture. In particular, he wanted someone local to make a light balloon, which was currently being researched in the West, and to fly it above Kyoto. He approached Makimura with this conception, and after receiving strong support, requested that Genzo, who had gained the trust of the Physics and Chemistry Research Institute, manufacture the balloon.

It was early summer, 1877. It was decided that the flight would be at year end.

Amidst the Accolades

From that day forward, Genzo began a period of trial and error. Hydrogen, which is lighter than air, was required to get the balloon to fly. Genzo requested eleven 72-liter barrels and one even larger barrel from the sake brewery in Fushimi, next to the city of Kyoto, and then used them to develop a gas generator by placing scrap iron in them and pouring dilute sulfuric acid over it. At the same time, coming up with a material for the balloon that would contain hydrogen gas was a real headache. He tried grinding up konnyaku (a gelatinous food made from devil’s-tongue starch) and applying it to paper or cotton cloth, but this turned out to be too heavy. He then had the idea of coating the thin cloth used for kimonos with dammar gum (a kind of tree sap) dissolved in perilla seed oil. This not only kept the hydrogen in but was also lightweight. Several months passed, and the balloon was completed.

On the morning of December 6, 1877, a large crowd of 48,000 people gathered at the old Kyoto imperial palace, the venue for the balloon’s first public appearance. The hydrogen gas produced in the sake barrels gradually filled the balloon, and the balloon with its human passenger rose 36 meters into the sky. This spectacle brought smiles to the faces of the people of Kyoto who had suffered so much. At the same time, it symbolized the beginning of the scientific age. Both Makimura and the spectators were not shy with their applause. The success of Japan’s first civil balloon flight was two years after Genzo founded Shimadzu Corporation.

Honing the grasp of science and technology, aiming to realize a future like no one had ever seen...even today, this remains the essential attitude at Shimadzu. Just as Genzo had made the scene of someone floating up into the sky a reality, Shimadzu reveals a never-before-seen world of science, making the depths of the human body visible. It fearlessly challenges itself even in the face of the completely unknown if it can contribute to society in the process. In fact, that very novelty is likely what piques its curiosity and leads it to take on the challenge.

At the end of the Shimadzu Science Equipment Catalog List, published in 1882, are the words “We will gladly undertake the manufacture of whatever you may request of us.” This no doubt encapsulated Genzo’s wish to hear about a future that would lift people’s spirits, and to build an exciting future together with them.

Related Link

On March 31, 2025, Shimadzu Corporation celebrated its 150th anniversary since it was founded.

Click here to view the commemorative website.

Shimadzu Corporation 150th Anniversary Website

- *This article is an English translation of our article originally published on the website “Boomerang”.

Copied

Copied