A Paradigm Shift Takes Its First Breath

Humans breathe not only oxygen, but sulfur as well.

Research in Tohoku University is overturning everything we thought we knew about life.

Ahead lies a transformation that could fundamentally change drug discovery, healthcare, and well-being.

Questioning Common Sense

Ask anyone about breathing, and they will answer that we inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide. Some people might even describe cellular respiration as using oxygen and nutrients such as glucose in mitochondria to produce energy, while carbon dioxide and water are expelled as waste products.

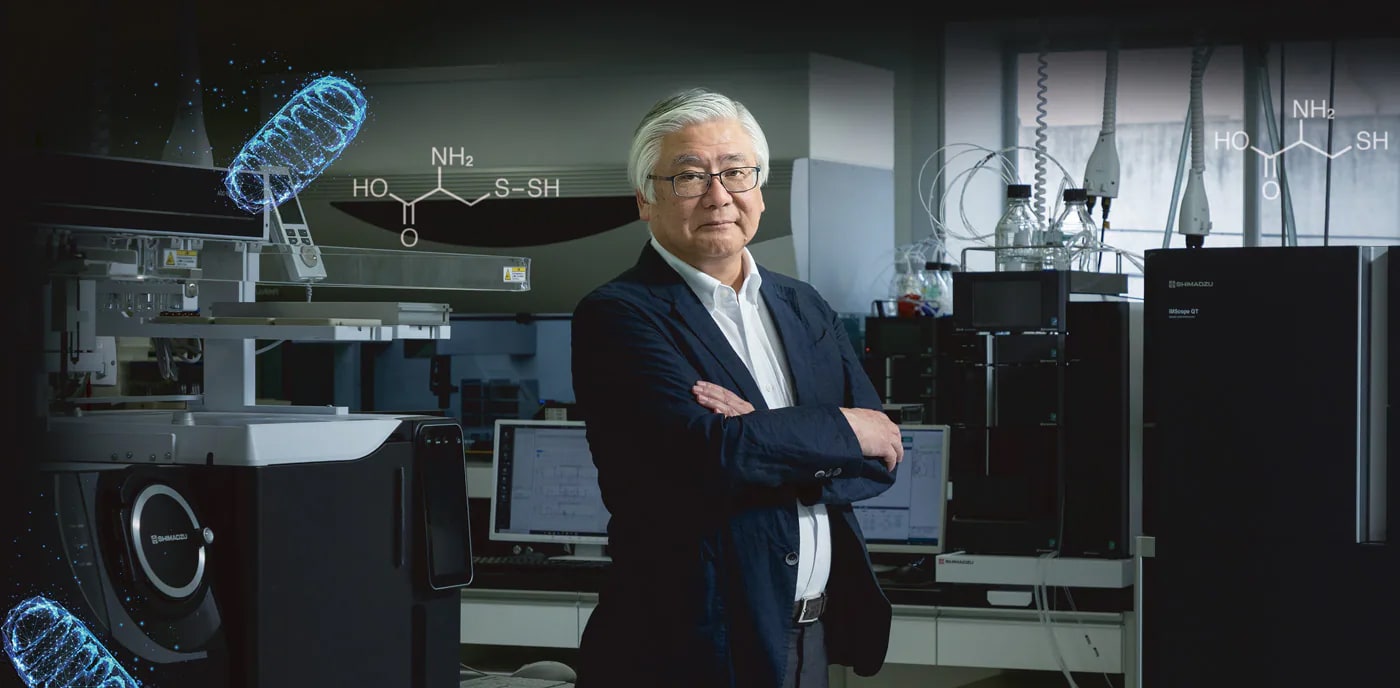

But very few people would nod in agreement if told that cells breathe not only oxygen, but sulfur. And it is not just about microorganisms living near undersea volcanoes spewing sulfur—hearing that this occurs inside the bodies of mammals, including us humans, would probably surprise most people. The discovery was made by Professor Takaaki Akaike, Graduate School of Medicine, Tohoku University. In 2017, his findings were published in the journal Nature Communications.

“When a close acquaintance jokingly told me, ‘Professor, you’ve written quite a fanciful novel.’ I felt quite awkward,” he recalls. “Everyone thought, ‘That kind of research is far too far out,’ or ‘That’s impossible.’ Yet it turned out to be a major discovery,” he said, his face breaking into a smile.

Two billion years ago, before algae appeared and began generating vast amounts of oxygen, there was no oxygen on Earth. Even so, life existed, so it must have had some way of breathing to obtain energy. And since microorganisms that use sulfur as an energy source still exist today, many believed sulfur once served as a substitute for oxygen. However, mammals—highly evolved animals—were believed to produce energy only through oxygen respiration, with no link to sulfur respiration.

Yet scientists had long puzzled over phenomena that oxygen respiration alone could not explain.

“Tissues with high oxygen consumption, such as muscles, hematopoietic stem cells, and highly malignant cancers, often become hypoxic. Even so, they keep growing and generating energy. That means there must be an energy-producing pathway that doesn’t depend on oxygen. Many scientists believed there must be some other metabolic pathway and were searching for it.”

The Concept of Life is Changing

The true nature of energy in living organisms remains a subject of debate, with no definitive conclusion reached. However, it is well known that the “currency” which carries that energy is a molecule called ATP. ATP is produced in large quantities inside mitochondria using nutrients and oxygen. During production, hydrogen in carbohydrates and other nutrients is split into hydrogen ions (protons) and electrons. Hydrogen ions become essential building blocks for ATP, but the electrons create a problem. If left alone, they would simply recombine into hydrogen, so they must be disposed of quickly. Mitochondria bind them to oxygen, which serves as the final acceptor, and release water as the end product. In this way, mitochondria serve not only as “factories” for ATP production but also as “disposal sites” for unwanted electrons.

Even if oxygen were replaced by sulfur, the basic ATP production mechanism remains the same. ATP is generated when hydrogen protons bind to sulfur, while excess electrons bind to sulfur and are released as hydrogen sulfide. Hydrogen sulfide easily converts back into sulfur, so in practice, sulfur exists inside the body in that form.

One day, while at Kumamoto University, Professor Akaike noticed something intriguing.

Within mammals, large amounts of a sulfur-containing amino acid (cysteine) exist in a form with an added sulfur atom (cysteine persulfide). What does that mean? It suggested the hypothesis that humans synthesize cysteine persulfide internally, that is, we metabolize cysteine to make sulfur metabolites.

Later, Professor Akaike established a method to detect sulfur metabolites.

“There really is a large amount of sulfur inside the body. I’ve shown this to be true. Because oxygen is such an efficient electron acceptor, everyone had simply forgotten about sulfur. Yet mammals possess enzymes that break down toxic hydrogen sulfide and further reuse the resulting sulfur. This is beyond doubt.”

More surprising discoveries followed. Professor Akaike’s team created mice with defects in a part of the metabolic pathway required for sulfur respiration. Around three to four weeks after birth, their growth sharply declined. This demonstrated that sulfur respiration, far from being unnecessary, is essential for mammalian development.

Oxygen respiration inevitably creates reactive oxygen species. These damage cells and contribute to aging. Sulfur, however, prevents this self-inflicted oxidative damage. If methods can be developed to control sulfur respiration, we may be able to boost energy production in the body, prevent aging, and develop preventive and therapeutic treatments for intractable diseases. It is even possible that sulfur metabolites could serve as cancer markers and be used for cancer prevention and treatment. This discovery has the potential to spark a paradigm shift in healthcare and drug discovery.

Toward Social Implementation

“As a student, I pushed myself to study hard, thinking that although I might never make it to major international sports competitions as an athlete, maybe, just maybe, I could win a Nobel Prize someday,” said Professor Akaike.

Though that is not entirely a joke. He devoted himself to swimming in his youth and made a name for himself throughout the prefecture.

He entered medical school and even worked in emergency care as an intern, but chose to pursue research and went on to graduate school. He was assigned to an infectious disease group, where he focused on research into innate immunity and reactive oxygen species. There, he quickly established a reputation as a rising talent, advancing on the elite track at the School of Medicine, Kumamoto University.

“I was sent on assignment to Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology as a leadership trainee, and I was even told I might become the dean of the School of Medicine one day, but that sort of role just wasn’t for me.” In 2013, his ninth year as a professor, he accepted an invitation from Tohoku University, on the condition that he could continue his research.

After moving, he devoted himself entirely to sulfur respiration studies. His research career looks fulfilling, yet he always felt conflicted.

“It is honestly frustrating. My classmates became doctors, saving many people. However, I decided not to pursue a clinical career and focused only on basic research. If I want research to save people, it has to reach society.”

Shimadzu × Tohoku University Supersulfides Life Science Co-Creation Research Center

It was with this in mind that Professor Akaike assumed the position of Director of the Shimadzu × Tohoku University Supersulfides Life Science Co-Creation Research Center, jointly established by Tohoku University and Shimadzu Corporation in 2024. The goal is to contribute to society by exploring sulfur-bound organic compounds with powerful antioxidant properties, and from there build pathways for diagnosing and treating various diseases, and developing functional foods.

“Research cannot be done alone. To gather collective effort, we must build a theme everyone accepts. If others can’t enjoy the work, neither can I. The project here has a very interesting theme, so I think we can expect good results.”

The day when Professor Akaike’s “exciting research” astonishes the world no longer seems so far away.

Takaaki Akaike, Distinguished Professor, Department of Redox Molecular Medicine, Graduate School of Medicine, Tohoku University; Director at Shimadzu × Tohoku University Supersulfides Life Science Co-Creation Research Center

Born in Kumamoto Prefecture. Graduated from the Faculty of Medicine, Kumamoto University in 1984 and completed a PhD in Medical Sciences at Kumamoto University Graduate School in 1991. Served as Associated Professor at Kumamoto University, Visiting Professor at Thomas Jefferson University and the University of Alabama at Birmingham in the United States, and Program Officer (Scientific Research Senior Specialist) at Research Promotion Bureau of Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. Appointed as Professor at Graduate School of Medicine, Kumamoto University in 2005. Became Professor at Graduate School of Medicine, Tohoku University in 2013, and has held his current position since 2024.

- *This article is an English translation of our article originally published on the website “Boomerang”. The information, including affiliates and titles of the persons in this article, are current as of the time of interviewing.

Copied

Copied